You know that feeling when you know something is off but you cannot figure out what it is? Like you’re looking at a friend and can’t figure out why they are different, then you look deep into their eyes and feel a love that you have never felt before…or just notice that they have a new haircut or got new glasses or something? That’s “uncanny.” Uncanny is difficult to define because it is a feeling of the indescribable, but it has been part of our vocabulary since the beginning of the twentieth century.

Ernst Jentsch’s “On The Psychology of the Uncanny” (1906) defines uncanny as a “lack of orientation,” where a person who is experiencing this phenomenon is not quite familiar with their current situation. To Sigmund Freud, defining a word as an uncertainty was not sufficient, so he develops it more in his book titled “The Uncanny” in 1919. Freud brings a more abject rendering of the word, describing it as an effect of experiencing repetition where our repressed impulses bubble to the surface. His use of the German word unheimlich, or “un-home-like,” brings an image of a secret, or something that is hiding in plain sight.

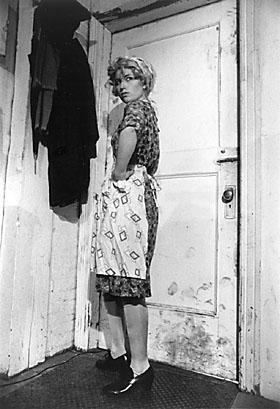

Artists explore the uncanny through slight shifts in reality. My favorite example of uncanny art is Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Stills” series (1977-1980). “Untitled Film Stills” is 69 black and white photographs of Sherman dressed as stereotypical Hollywood female characters. Every character is a person you swear you have seen before (the cheerleader, the housewife, the damsel in distress), but every woman is fiction, an image of our collective imagination. Her photographs rely on the uncanny, an image of the familiar that upon closer inspection becomes foreign.

Otto Umbehr, known as “Umbo,” created uncanny artwork through formal affects. I was exploring the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s photography collection online and stumbled upon a photograph by Umbo. “Uncanny Street I (Unheimliche Strasse I)”, is an aerial shot of a German street. The angle chosen by the artist, which is completely parallel to the street, causes the work to be unrecognizable as a street initially; the large black figures and shades of gray create what looks like a collage, different textures pieced together on a page. Look closer, and these dark figures are long shadows shooting off of a man walking on the sidewalk, a man on a bicycle, and nearby buildings. Umbo turns an easily recognized space, a street, and makes the subject its shadow.

-unheimliche-strasse-(uncanny-street)-(from-the-umbo-portfolio).jpg)

When we get stuck in our routines, like our daily commute, we become numb to the details. It takes big changes for us to take a second look. Remember that weirdness we had with our surroundings after the election? Ryan Hamilton in his new Netflix stand-up “Happy Face” summed up that feeling perfectly.

I had never heard of Ryan Hamilton prior to watching his new stand-up special, and I have to say that I’m glad I know him now. “Happy Face” tells the stories of a man from a 1000 person town in Idaho now living in Hell’s Kitchen New York. Two very different places, but to him it’s a strange time to be from anywhere in the U.S. In New York, Hamilton hears people say “I don’t know who all of these Trump voters are.” Hamilton’s reply: “I’m from a town of one thousand in Idaho. I know who they are.” He then goes on to describe the day after election night in November. Here’s Hamilton’s experience:

I haven’t had a conversation in a very long time that hasn’t ended with ‘well it’s going to be interesting.’…I will never forget election day… But the next day was the strangest day of all. You went home, you slept for four fitful hours, then you woke up wide-eyed, and walked over to your window and you looked outside and went ‘well it looks okay, I guess. I guess I’m going to go out there.’ And then you left your home and that was the strangest feeling on the strangest day, wasn’t it? Just walking outside like ‘Here we go! Out into the new normal!’ Just making eye contact with people, like ‘I don’t know, I’m going to work, I guess!’

After I heard this segment I immediately thought of the uncanny. After November 8, 2016, we all felt unfamiliar in our familiar surroundings. Leaving the house and walking on the street, everything looked exactly the same but everything was different. It was like we were all looking at our streets at parallel; the extended shadows revealing the ugliness that we had denied existed. The darkness stretched out before us, we all still moved forward with this uncanny feeling, thinking “well it’s going to be interesting…”

Freud, Sigmund, David McLintock, and Hugh Haughton. 2003. The uncanny. New York: Penguin Books.

Jentsch, Ernst. “On the Psychology of the Uncanny (1906).” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 2, no. 1 (1997): 7-16.